66. Chess in Germany since the 18th c.

Historical facts

About 1970 faced with the hundreds historical major and minor chess facts collected by the English chess player Harold Murray in his standard work about the history of chess (1913), I was lulled to say so. ‘What a terrific game, chess’, I thought, ‘unequaled’. My grandfather, a club chess player, told me time and again the same from the day I spoke hundred words and understood thousand words: “Chess is a game for kings. Mankind did not invent a deeper and richer game”. I readily believed Murray and grandpa.

“Draughts springs from chess”, was Murray’s message in a second standard work (1952), brought with certainty. Again I internalized his words, he was the big expert. Until some sunny days during the summer holiday of 1975, when I rode on my bike to the library of Rotterdam and found that Murray’s certainty was far from certain.

In 1985 another English chess player published a new standard work on the history of chess; his name is Richard Eales. He applied the same method als his forerunner by bombarding the reader with hundreds of major and minor chess facts. See chapter 63 for the abundance of English material from the 19th c.

Murray was an enthusiastic chess man, trying to convince the reader by a bombardment of historical facts of the excellence of chess in the European culture. Eales phrases his purpose in the opening sentence of his Preface: “A history of chess is firstly a history of chess players” [Eales 1985:9]. Ergo: a series of facts.

Eales gives some facts about 19th c. Germany. I give a supplement.

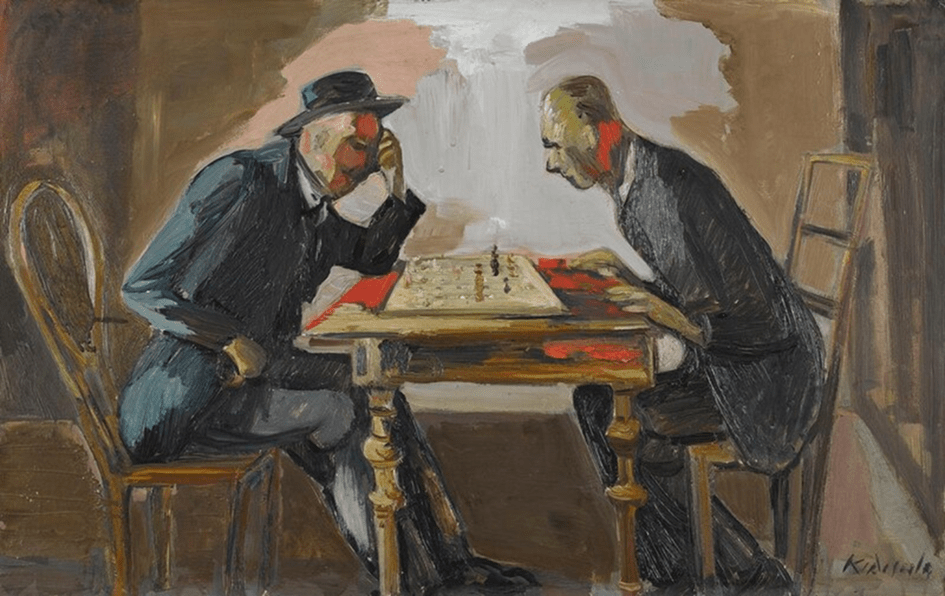

Karl Aegerter (Germany 1888-1969)

Chess clubs

Chapter 62 and chapter 63 described the rise of chess in France, the Netherlands and England. There seems to have been an identical development in the Netherlands and in England: middle-aged middle class gentlemen looked out for a pretext to meet and found it in a chess club. What they ‒and we‒ called a chess club in actually was a society, a social happening. In Paris and London in the first quarter of the 19th c. members of the urban elite met in exclusive clubs. The main target was to meet important people, but also chess was played. Just as happened in Amsterdam ‒vdS. A strong chess player from a lower social class was not admitted [Eales 1985:127-8]. An identical pattern in Germany?

The German Wikipedia mentions the first ten German chess clubs. Or should I better write: societies where chess was used as a cop-out?

Berliner Schachgesellschaft 1827

Hamburger SK 1834

Münchener SC 1836

Elberfelder Schachgesellschaft 1851

Krefelder Schachklub Turm 1851

Karlsruher Schachfreunde 1853

Düsseldorfer Schachverein 1854

Schachclub Ansbach 1855Aachener Schachverein 1856

SK Giessen 1858.

The first chess manuals

Long before the foundation of these clubs (societies) textbooks were published, translations of the French books of Philidor [see also Eales 1985:120] and Stamma, traced on internet by the Dutch board game investigator Jan de Ruiter:

François-André Philidor „Die Kunst im Schachspiel ein Meister zu werden“ 1754, 1764, 1771

Philip Stamma “Schachspiel-Geheimnisse: nebst einigen Regeln“ … 1771, 1806

François Danican Philidor “Praktische Anweisung zum Schachspiel“ 1779, 1797, 1810, 1833, 1840

François Danican Philidor “Das schachspiel, oder, Sammlung interessanter spiele desselben“… 1834.

Eales [1985:119-20]: in Germany there was confusion of local chess rules, but little by little the publications of Philidor’s book caused uniformity.

Philip Stamma “Beyträge zum Unterricht im Schachspiel“ 1804

Ein geborener Alepper aus Syrien “Versuch über das Schachspiel: worin einige Regeln, um es gut zu spielen …“ 1812.

Is the next book a kind of pirate edition or does the author fulfil what he promises, an improved version of Stamma by a German chess player?: N.N. “Das Schach des Herrn Gioachino Greco Calabrois und die Schachspiel-Geheimnisse des Arabers Philipp Stamma: verbessert, und nach einer ganz neuen Methode zur Erleichterung der Spielenden umgearbeitet“ 1784. It is clear that there was German interest in chess, but is not clear on which scale ‒vdS.

Text books written by German chess players until 1840

Johann Christoph Ludwig Hellwig “Versuch eines aufs Schachspiel gebauten taktischen Spiels…“. Volume 1 1780, volume 2 1782

Johann Allgaier “Neue theoretisch-praktische Anweisung zum Schachspiel“. Deel 1 1795, deel 2 1796; 1802

J. K. Kindermann “Vollständige Anweisung: das Schachspiel …“ 1795, 1801

Adolph Julius Theodor Fielding (= pseudonym of J.G. Flittner “Neueste Art das Schachspiel gründlich zu erlernen“ 1797, 1804, 1818, 1819, 1820

Christian Gottfried Flittner “Neueste Art das Schachspiel gründlich zu erlernen“ 1812

Johann Friedrich Wilhelm Koch “Codex der Schachspielkunst“ Deel 2 1813

Joseph Karl Kindermann “Vollständige Anweisung, das Schachspiel durch einen …“ 1819

Joseph von Ranson “Anweisung zum Schachspiel, nebst Kritik desselben …“ 1820

William Stopford Kenny “Der Schachgrammatik: oder, praktische Anleitung zum Schachspiel“ … 1821

Domenico Lorenzo Ponziani ”Das Schachspiel” 1822

V. Mosler “Das Schachspiel: Mit 7 Kupfertafeln“ 1822

Johann Horny “Anweisung das Schachspiel gründlich zu erlernen“ 1824, 1828

Otto von Deppen “Schach-Politik, oder Grundzüge zu der Kunst, seinen Gegner im Schach bald zu …“ 1826

Friedrich August Wilhelm Netto “Shatranj oder Das Schachpiel unter zweien … 1827

G. Crailsheimer “Neue praktische Anweisung zum Schachspiel“ 1829

Karl Friedrich Schmidt „Hundert und Zwanzig Schach-räthsel…“ (combinations) 1829

Giambattista Lolli “Beiträge zum Schachspiel“ 1833

Christian Friedrich Gottlieb Thon “Der Meister im Schachspiel…“ 1840

Friedrich Theodor Winterfeld “Practische Anweisung sich im Schachspiel…“ 1840

A few other publications

In the egg two methods were published to play chess with four persons:

K.E.G. “Theoretisch-praktischer Unterricht im Schachspiel unter Vieren …“ 1784

C. Senfft von Pilsach “Das Belagerungs-schach: mit einer Anweisung zum Schach unter drei und vier Spielern“ 1820.

Further chess poems appeared, among which a translation of the 16th c. Latin poem of the Italian Marco Girolamo Vida, and prose works about chess.

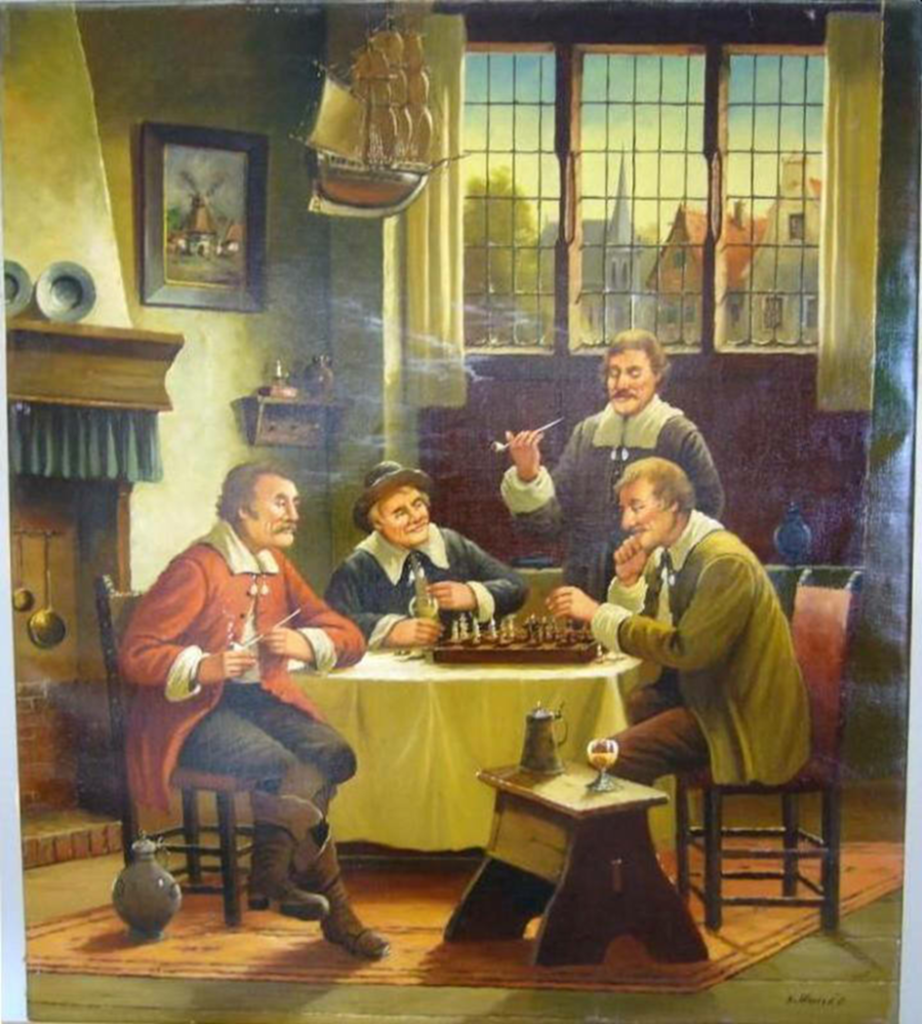

Karl Andree (Germany)

Buy but not play?

In France and England chess players bought Philidor’s book, but without the intention to learn to play chess; only in the late 19th c. in England, and in the Netherlands also, chess clubs were founded as we know them in our days. The same happened in Germany: German chess players bought manuals long before chess clubs were got off the ground.

The phenomenon induces a question: did these chess players possess a chess board? At least half a century ago in the Netherlands historical materialism split off from history science, i.e. research into household goods, included the gaming board, so included chess boards. In the Dutch context this is possible because the chess board with its 64 squares differs from the draughts board with its 100 squares. In France, Great Britain and Germany such research does hardly exist. But even if it will be set up, there is the problem that draughts and chess are played on the same 64 squares board.

German followed the same path as England, Eales found: players founded clubs. Chess began to appeal to a much wider section of society. In 1887 the number of chess clubs allowed Germany to found a national chess association. Large national tournaments were organized. In the second half of the 19th c. there were international tournaments, the first one in 1851 [Eales 1985:142]. It sounds great, international tournament, but a player had to defray the cost of his participation [Eales 1985:145].

In passing Eales [1985:119-20] notices: regionally German players applied different rules, but under influence of Philidor uniformity rose.

Like in England chess was a game for and of middle class people. Before 1914 there were efforts to found working men’s chess clubs. With some success: in 1912 sixteen of those clubs began publishing the “Arbeiter-Schachzeitung” [Eales 1985:148-50].

Owing to all these initiatives Germany could grow into Europe’s third force in chess after England and France [Eales 1985:136].

The German chess historian Joachim Petzold cherished a more enthousastic view of chess. He considers chess as an important factor in the European culture and is with this view Murray’s kindred soul. “More than once chess reacted as a seismograph to social changes”, he let us know [Petzold 1986:151] ‒I restrict myself to one example. That is why he sees the introduction of the new chess queen in the late 15th c. as a reaction to the great social changes initiated by giants as Martin Luther, Desiderius Erasmus and Christoffel Columbus [Petzold 1986:152]. Down-to-earth linguistic objection: this new chess queen is a reaction to the long queen in Spanish draughts and the name for the new piece was borrowed from the jargon of French draughts players, see chapter 4.

The Dutchman Hans Scholten, going into details, described the rise of chess in the 19th c. Netherlands and so did Richard Eales for England. A German study of this kind is lacking. Petzold restricted himself to a summary of the development of organized chess and the national and international tournaments resulting from this organization [Petzold 1985:209-14].

The pictoral arts and chess in Germany

In 2021 the study “Chess, Draughts, Morris & Tables. Position in Past & Present” was published. Responsible authors Arie van der Stoep, Jan de Ruiter and Wim van Mourik. 369 pages, thick half glossy pages, hardcover, 375 full color reproductions of among others paintings and drawings of German artists pictering chess and three other board games. This book is a supplement to the description of chess above.